Did you know that the word “haiku” was born only at the end of the 19th century?

Let’s sort out this famous form of Japanese poetry.

.

Waka, uta and renga, the ancient Japanese poetry

Poems made by five and seven syllables verses were already common from the 18th century,. They were called with various names, among which waka or uta, that are general terms for “poetry”.

Moreover there was a particular form of collective poetry, called renga, or “poem in dialogue” (“ga” is a different reading of “uta” kanjii) where two or more persons interchanged improvising couples or tercets of verses – called “ku”- answering one to each other.

The haikai

About the 14th century a new kind of renga, called “haikai no renga” or shortly “haikai”, spread. It was a more free, popular and less refined form of renga (“haikai” means “funny” or “comic”).

Haiku comes from this form of poetry; the term itself is the contraction of “haikai no ku” (verses of haikai).

The first tercet of verses of an haikai was called “hokku” and it was made by 5-7-5 syllables verses. It was the haikai most important tercet because it defined the topic and the nature of the whole poem.

Matsuo Basho and the Edo period

At the time of Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), hokku had become a “poem into the poem”, a short but intense expression that could be read independently from the rest of the poem.

Basho lived at the beginning of the Edo era, a period of peace after years of internal civil wars. In Japan a new urban middle-class arose at the time. It was interested in new and simpler kinds of art, like ukiyo-e, illustrated novels (ukiyo zooshi), kabuki theatre and a less elevated, but not less refined, form of poetry.

Basho led the haikai from a brilliant expression to a deeper and felt one.

Basho was an haikai master and he organized poetry meetings in Tokyo. At some point in his life he chose a wandering, solitary and poor life, to deepen the zen philosophy knowledge.

Basho’s poetry was then influenced by zen aesthetics, full of wabi-sabi, which is the taste for a sober, flawed and wistful beauty.

The haiku

The haiku is made up of three verses of 5, 7 and 5 syllables.

Few concise verses, filled by everyday life images, in which you can recover the relationship between man and nature, between universal and passing beauty, the reflection of the eternity in every moment of everyday life.

Haiku comply with several formal standards, among which the most important one is that of including a “kigo”, a seasonal element. It can be a flower, an astronomical reference, the fireworks of a seasonal celebration; this choice specifies the time of the year during which the described scene is held and gives a specific sense to the meaning of the story.

The haiku conciseness is not the result of an extreme synthesis, but of a contraction; it’s a removal of all the elements that, although unsaid, are understandable. In its semplicity, the haiku doesn’t refer to metaphysical or ideal meanings; it simply tells about an occurrence or, better, a motion, something evolving that happens in no time. A life moment that finds its uniqueness in raising a marginal and ordinary element to a model of beauty.

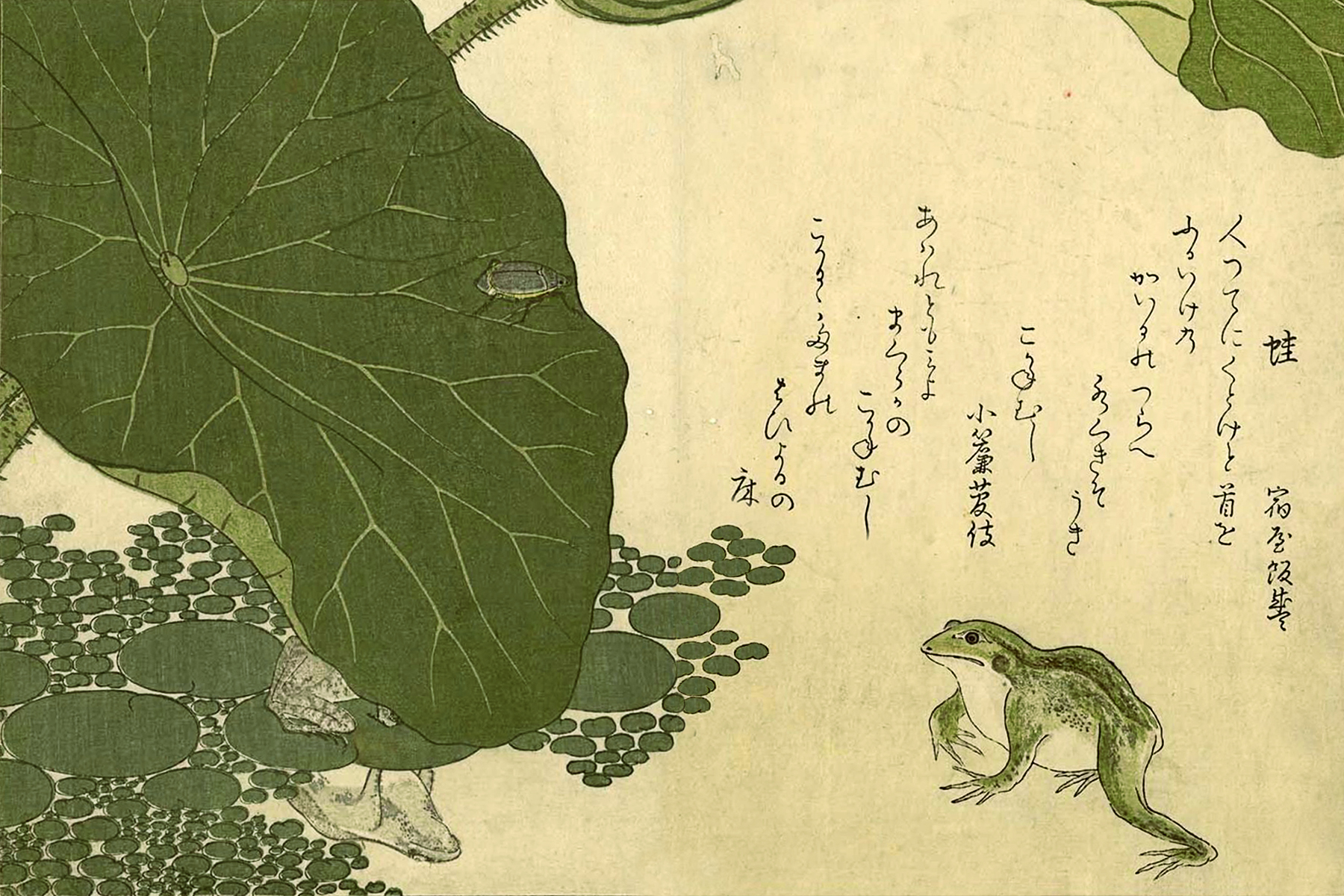

The ancient pond

The ancient pond.

A frog jumps.

The sounds of water.

The haiku we chose to name the meeting we hold in our studio (“The sound of water” at La quarta corda studio) was written in 1686 and the mentioned pond is the one near poet’s house. The frog is the seasonal element, the “kigo”; the poem takes place in spring, when frogs emerge from hibernation and reproduce.

These few verses are a high expression of wabisabi; the love for simple things that make us wonder and concentrate on a single moment that was about to be lost. It’s the beauty of the patina that reveals the flow of time, like the moss on the stones that we can imagine near the pond.

This sense of peace is suddenly interrupted by a jumping frog. This motion shifts our focus to the sound of the ripple on the water’s edge.

Our thoughts start to move, comparing the old pond slow time with the frog fast one, the standstill and the motion, the silence of the stagnant water with the sound of the jumping frog. This inexplicable fascination is “yugen”, a mysterious depth, an elegant and complex naturalness.

The figurative element of the pond, the cinetic one of the frog and the auditive one of the water shall coordinate; the three verses wouldn’t exist one without the other.

At the end everything comes back to how it was.

In Japanese it is called “mono no aware”, the sweet melancholy, the nostalgia about what is changing, the feeling for something that is immutable and fleeting together.

.